The British Museum is known for housing a vast collection of artifacts from across the globe. But what was the way some of these treasures were acquired? That’s where things get a little complicated.

Today, we’ve compiled a list of truly fascinating pieces, spanning cultures from China to Kenya. Each one has its own story to tell, and not all of them come without controversy. Curious to see what’s inside? Keep scrolling for a glimpse into the marvels and the mysteries they hold.

#1 The Elgin Marbles

In the early 19th century, the Elgin Marbles, a collection of sculptures dating back 2500 years, were taken by a British diplomat from the Parthenon in Greece. He sold them to the British government, which then shipped them off to the British Museum. Believing the marbles were looted, the Greek government listed a dispute with UNESCO over their return, but the British government declined the organization’s attempt at mediation. Today, the Elgin Marbles remain in the British Museum, and discussions between the two countries regarding their return are in progress.

Image credits: Marie-Lan Nguyen

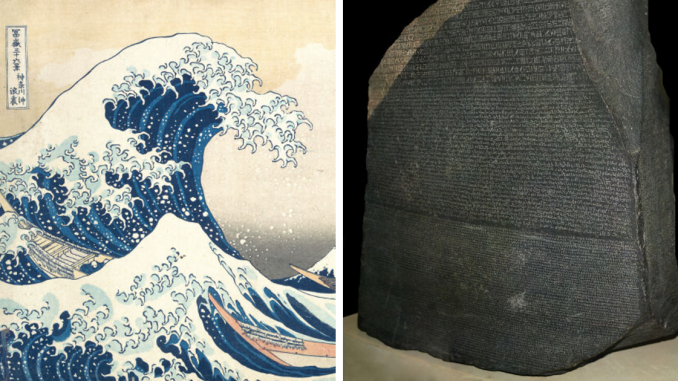

#2 The “Under The Wave Off Kanagawa” Print

Katsushika Hokusai is one of Japan’s most revered and innovative artists. Hokusai’s painting “Under the Waves off Kanagawa,” also known as “the Great Wave,” is considered his best work. The painting is a color woodblock print depicting an enormous wave crashing down on three fishing boats off the coast of Kanagawa. One of the surviving prints of “Under The Wave Off Kanagawa” and many of his other works are displayed at an exhibition called “The Great Picture Book of Everything” in the British Museum.

Image credits: Katsushika Hokusai

#3 The Lamassu

The Lamassu is a statue of a winged lion or bull with a human head that was placed in front of the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal in Nimrud as a symbol of protection. Acquired by the British Museum in 1851, the statue dates back to 865 BC and was excavated by Austen Henry Layard. Other Lamassu statues are housed in museums across the world, such as the National Museum of Iraq and the Louvre Museum.

Image credits: Poulpy

The British Museum states on its official website that its collection has been built through a variety of means. Some pieces, however, have drawn attention due to their disputed origins and have even been subject to requests for repatriation by other countries. This ongoing debate continues to raise questions about rightful ownership tied to cultural artifacts.

A considerable part of the museum’s holdings came from donations or bequests, especially throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. One notable example is the Sutton Hoo collection, a magnificent Anglo-Saxon ship burial discovery from 1939. Edith Pretty, the landowner of the site, donated the entire find, contributing significantly to the museum’s medieval treasures.

#4 The Glazed Dragon Tiles

This collection of 20 glazed tiles, made during the Ming Dynasty, once adorned the roofs of small buildings in a temple in Shanxi, China. Seen as a symbol of protection against fire, the tiles are arranged in two rows, one with yellow dragons and the other with blue dragons. The colors and designs of the tiles also symbolize Chinese beliefs in the powers of Yin and Yang. The British Museum acquired them in 2006, and they have been on display ever since.

Image credits: B

#5 The Hoa Hakananai’a Head

The Hoa Hakananai’a Head, a moai statue, was stolen from Orongo Easter Island in 1868 by a British Royal Navy ship crew and taken to the British Museum. The Rapa Nui people consider the statue as stolen and in 2018, the governor of Easter Island requested that the British Museum return it to them. Discussions to repatriate the statue have since stalled, and it remains in the British Museum.

Image credits: James Miles

#6 The Tsavo Lions

The Tsavo Lions, also known as the Tsavo man-eaters, were a pair of maneless male lions in the Tsavo region of Kenya. They were responsible for over one hundred human fatalities on the Kenya-Uganda Railway in 1898. British Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson eventually did away with the lions in December that same year. Patterson kept their skins as rugs in his home until he sold them to the Field Museum of Natural History in 1924. Today, after being reconstructed, the lions are on display at the museum along with their skulls.

Image credits: Superx308

Generosity hasn’t waned in modern times either. In 2003, Alexander Walker, a prominent film critic for the Evening Standard, bequeathed a remarkable collection of modern prints and drawings. His donation included works by artistic giants like Matisse and Bridget Riley, further enriching the museum’s 20th-century archives.

#7 The Early Shield From New South Wales, Australia

The Aboriginal Australian shield, presumably originating from the coastal regions of New South Wales, dates back to the late 1700s and was made from the bark of the red mangrove plant. It has a distinct hole near the center, most likely from being hit by a spear. Despite several requests from Aboriginal communities for its return to Australia, the shield remains at the British Museum in London.

Image credits: geni

#8 The Beard Of The Sphinx Of Giza

In the 19th century, fragments of the Beard of the Sphinx of Giza were discovered in the debris surrounding the base of the iconic sculpture. According to the British Museum, the beard was likely an enhancement added to the Sphinx by King Thutmose IV. The piece is currently located in the British Museum while other fragments are housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Image credits: Captmondo

Many other items in the British Museum have come from archaeological excavations across the globe. These digs, which continue today in regions from the Caribbean to the Nile Valley, aren’t just about acquiring relics: they aim to answer research questions and provide deeper historical context to existing collections.

#9 The Gold Crown Of Maqdala

In 1868, after capturing the city of Maqdala, the British brought back many royal treasures. Of these treasures, the regal and highly detailed gold Crown of Maqdala was the most valuable. Currently owned by the Victoria and Albert Museum, the crown has been the subject of restitution claims made by Ethiopia since 2007. Many other royal treasures, far less significant than the crown, have since been returned to Ethiopia.

Image credits: FredHarter

#10 The Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a fragment of a larger black basalt stone slab dating back to 196 BCE that was discovered by French troops in 1799. It contains a decree about King Ptolemy V written in Egyptian hieroglyphics, Demotic language, and Greek. The stone made its way to the British Museum in 1802 and remains one of its most famous pieces despite Egypt’s many attempts to reclaim it over the years.

Image credits: Hans Hillewaert

Despite these legitimate contributions, many of the museum’s most famous and controversial pieces are of foreign origin. As Euronews highlights, although England contributes the largest volume overall, it’s often the globally sourced items that spark the loudest calls for return.

#11 The Admonitions Of The Instructress To The Court Ladies

In 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion in Beijing, Captain Clarence Johnson acquired a silk scroll depicting a poetic narrative painting by the poet Zhang Hua. This scroll was called the Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies, and its text was aimed at correcting the behavior of an empress. Johnson then sold the scroll to the British Museum, which only displays it for six weeks every year due to its sensitivity to light.

Image credits: Gu Kaizhi

#12 The Lewis Chessmen

The Lewis Chessmen are a group of chess pieces from the 12th century, carved from walrus ivory. After their discovery in Scotland in 1831 and exhibition that same year, 67 chessmen and 14 tablemen of the 94 objects available were purchased on behalf of the British Museum. As of today, 82 pieces are exhibited in the British Museum, 11 at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, with the last chess piece privately owned.

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

One of the museum’s harshest critics is Geoffrey Robertson, an Australian-British barrister and human rights advocate. He has condemned what he terms the museum’s “unofficial stolen goods tour,” pointing to pieces like the Elgin Marbles (claimed by Greece), Hoa Hakananai’a (from Easter Island), and the Benin Bronzes (claimed by Nigeria).

#13 The Benin Bronzes

In the 1500s, a group of brass and bronze sculptures known as the Benin Bronzes was made in the West African Kingdom of Benin. Many of the pieces were used in ancestral rituals during that time. The artifacts were plundered by British troops in 1897 and were sent to the British Museum and other European institutions. Today, the Benin Royal Court has called for the return of the sculptures, but no plans have yet been made to fulfill its requests.

Image credits: Geni

#14 The Asante Gold Regalia

The Asante Gold Regalia comprises more than 200 gold items, including jewelry, royal insignia worn by the King of the Asante people, and badges worn by his officials. Many of the pieces were looted from Kumasi, the Asante capital, during the war in the 1800s. While some were sold to the British Museum, others formed part of a forced British indemnity payment. The remaining items were acquired by other museums and even some private collectors.

Image credits: Daderot

Whether taken through conquest, colonialism, or negotiation, the history of these artifacts is complex. Many hold deep historical, cultural, and emotional importance for their places of origin. The question remains: Should such items be returned to their homelands, or does the museum serve a broader purpose in preserving and showcasing global heritage?

Which of these historical pieces do you think holds the strongest case for being returned? Or should they remain where they are for global education and access? Let us know what you think.

#15 The Oxus Treasure

The Oxus Treasure is a collection of 180 pieces of silver and gold that were found in the Oxus River between 1877 and 1880. Said to be from a larger collection of around 1500 items, the pieces date back to the 5th century BC. Currently, the British Museum holds the surviving collection, which includes a gold model chariot, a pair of armlets, and other metalwork.

Image credits: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg)

#16 The Animal Mummies

The British Museum houses one of the largest collections of animal mummies in the world, with around 500 examples of cats, crocodiles, fish, snakes, and more. Originating in Ancient Egypt, these mysterious mummified animals were excavated in large numbers across different sites in Egypt. The crocodile mummy excavated in 1895, at Kom Ombo, Egypt, hasn’t been on display at the British Museum for 75 years. This is due to the complex conservation processes required to keep it intact for future exhibitions.

Image credits: Mario Sánchez